N,N-Dimethylformamide: A Practical Commentary on Its Role, Risks, and Future

Historical Development

The story of N,N-Dimethylformamide (DMF) runs deep, stretching back into the industrial chemical revolution. I remember digging through stacks of technical papers for a university project and finding references to DMF in research journals from the 1950s. The initial breakthroughs for this solvent came as chemists searched for something that could break down tough compounds, especially polymers. At a time when plastics and synthetic fibers were just beginning to change the world, DMF brought a solution to stubborn dissolution problems. Its popularity grew alongside innovations in pharmaceuticals, dyes, and electronics. Factories worldwide adopted the material as they needed something that could offer both strong solvating power and manageable volatility. This wasn’t about optical purity or exotic features; DMF gained its reputation by reliably delivering what early industrial chemists needed.

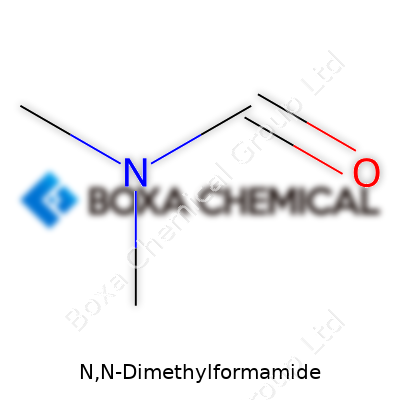

Product Overview

N,N-Dimethylformamide, often abbreviated as DMF, typically appears as a colorless, clear liquid that gives off a faint fishy smell. Lab techs and process engineers know it for the way it dissolves everything from acrylates to rubber. It’s a favorite in the production of polyurethane coatings and adhesives. DMF also shows up in solvents for spinning synthetic fibers and for manufacturing pharmaceuticals. This isn’t some niche chemical locked away in select labs; factories large and small continue to order it as a workhorse for daily operations.

Physical & Chemical Properties

The properties of DMF help explain its wide range of uses. With a boiling point over 150°C and a melting point just below zero, storage and shipping remain pretty straightforward compared to other organic solvents. It mixes with water and almost any organic liquid, so you won’t see clumping or delamination problems in the lab. I’ve spilled a bit of DMF on the bench in my time, and the evaporative odor lingers longer than you’d expect, warning you to keep the hood running. Its low viscosity helps with fluid transfer in industrial setups. From a chemical perspective, DMF’s amide group lets it take part in plenty of useful reactions. The compound’s low nucleophilicity and high polarity make it essential for tough couplings and carbonyl chemistry.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Suppliers sell DMF in different purity grades, usually topping out at 99.5% for high-end applications such as drug synthesis or electronics manufacturing. Labels show key thresholds for water, acidity, and other amines that might compromise final yields. Safety information jumps off the page—flammability, toxicity data, and shelf life—because jobs involving DMF always come with risk. Drums and bottles arrive stamped with symbols for both hazardous and environmental warnings. Regulated shipping practices became stricter in recent years due to stricter occupational safety laws and international shipping standards.

Preparation Method

The classic route to DMF in plants involves reacting dimethylamine with carbon monoxide. Synthesizing DMF demands careful control of temperature and pressure, with conditions skewed toward minimal by-products. One of my old professors walked me through pilot plant diagrams showing how operators use a continuous process for better yields. Alternative methods do exist, like using methyl formate as an intermediate, but the industry has settled on the most reliable, scalable approach. Optimization comes down to minimizing water contamination and making purification energy-efficient. Waste handling gets just as much attention, considering the regulatory hammer coming down on chemical effluents.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

DMF acts as a solvent for many chemical transformations, including peptide couplings and nucleophilic substitutions. Organic synthesis researchers use it as both a reaction medium and, in some cases, a reagent. It can get hydrolyzed under acidic or basic conditions, forming dimethylamine and formic acid. Chemists also use DMF to push tough reactions where other solvents fall apart, especially with strong bases or nucleophiles. In semiconductor cleaning and electronics fabrication, modified forms of DMF do the trick when high polarity and thermal stability matter most. This isn’t just about pushing boundaries for its own sake—DMSO may offer alternative properties, but DMF holds steady in places where reactivity and solubility decide the outcome of a high-value process step.

Synonyms & Product Names

Walk through any chemical storeroom and you'll see DMF listed alongside synonyms like dimethylformamide or formic acid, N,N-dimethylamide. Trade names differ depending on the region or manufacturer. Product catalogs use designations such as DMF Anhydrous or DMF Pharmaceutical Grade, which refer to specific purity or water content. Some companies stick with standardized nomenclature, while others add a brand twist mostly for marketing to industrial buyers and bulk customers rather than bench chemists.

Safety & Operational Standards

Safety practices around DMF have gotten stricter over the last decade. Workplace standards like OSHA set low exposure thresholds—workers keep track of time inside the laboratory hood or on a plant floor. Short-term headaches, dizziness, and nausea linger in the background of every job involving DMF, reminding operators and lab techs to double up gloves and run air monitors. Engineering controls, including air change rates and leak detectors, anchor modern operational standards. Emergency treatments for skin and eye contact with DMF get drilled into teams before every batch run, based on lessons learned from minor and major exposures in decades past. Companies don’t stop at medical monitoring; they back up every chemical delivery and drum change with third-party inspections and digital incident reporting.

Application Area

DMF finds a place across textiles, pharmaceuticals, electronics, and adhesives. In synthetic fiber production, DMF solves the problem of dissolving tough polymers so extruders run longer without clogs. Drug companies turn to DMF for tough peptide bond formations, solvent extractions, and certain API crystallizations. Resin and adhesive manufacturers rely on its ability to dissolve diverse binders, making it essential for high-performance coatings and surface treatments. In the electronics industry, DMF handles cleaning and surface-modification steps for PCB fabrication and lithium battery cell assembly. I recall hearing from colleagues in the automotive sector who swear by DMF’s value in producing durable seat fabrics and wiring harness coatings. In every sector, substitution keeps getting harder since DMF does the job other solvents can't touch without big compromises.

Research & Development

Chemists and materials scientists keep searching for ways to fine-tune DMF's properties or discover greener substitutes. A major theme in recent R&D is lowering toxicity without sacrificing performance, as regulators raise the bar on environmental persistence and worker exposure. Teams are developing modified amide solvents and screening for biobased analogs that meet current processing needs. Progress remains steady but slow, since many processes that use DMF hinge on its specific reaction profile and solubility. In universities and industrial labs, efforts focus on reducing waste streams and recovering DMF for reuse—tactics that lower both costs and emissions. Patent filings have shifted toward process intensification and hybrid purification methods, aiming to minimize losses and containment failures.

Toxicity Research

DMF’s toxicity isn’t theoretical for those who’ve worked with it. Regular contact links to liver problems, reproductive risks, and skin irritation. Over the years, I’ve watched coworkers swap stories about better gloves and ventilation upgrades. Occupational medicine journals describe DMF’s absorption through the skin and its acute impacts on the liver, evident in blood tests after significant spills or leaks. Long-term exposure ramps up the dangers, which makes engineering controls and regular safety training non-negotiable across all types of operations. High-profile regulatory attention from the EPA in the United States and REACH in Europe has forced companies to report incidents and limit exposure in tough, enforceable ways. Labs and plants face more scrutiny, which in turn drives demand for less toxic alternatives and better PPE.

Future Prospects

DMF likely remains a mainstay for many industries, even as pressure grows from regulators, environmental groups, and chemists focused on safer alternatives. Emerging research focuses on tweaking DMF's chemical backbone to preserve key benefits with less risk. Many companies invest in systems for closed-loop recovery and in monitoring breakthroughs for early leak detection. Governments and private labs are pushing green chemistry initiatives to cut down reliance on amide solvents altogether, yet for now substitutions face high performance and cost hurdles. Experience shows that meaningful change comes in phases; incremental improvements in process control, toxicology research, and solvent recovery push the industry closer to safer, more sustainable production. The balance between utility and safety keeps evolving, shaped by real-world use, ongoing innovation, and the regulatory environment.

A Chemical Backbone for Modern Manufacturing

N,N-Dimethylformamide, often called DMF, shows up in more places than you’d expect. The clear liquid might not catch your eye in a bottle, but a lot of big industries would come to a standstill without it. Over a few decades, working around industrial sites, I noticed that folks who deal with plastics, textiles, and pharmaceuticals trust this solvent to get tough jobs done when water or alcohols just won’t cut it. They know DMF can break down stubborn molecules or blend the unblendable, letting chemical reactions run smoother and faster.

DMF in Pharmaceuticals: A Silent Enabler

Big pharma can’t look past DMF. Drugmakers turn to it when synthesizing active ingredients or specialty compounds isn’t working out with other solvents. For example, certain antibiotics and antiviral medicines form better when DMF is in the mix. DMF helps form the right chemical bonds and boosts yields. The Food and Drug Administration recognizes it as an approved processing solvent, as long as strict limits stay in place. Cleaning up after DMF isn’t trivial, though—manufacturers work hard to keep exposure within safe limits, as DMF can sneak through skin or air if you don’t respect its hazards.

Textiles and Plastics: From Fibers to Flexible Films

DMF leaves a mark on the clothes and plastics we use every day. Synthetic fibers, especially polyurethane and acrylic, would be tough to spin without it. DMF dissolves these polymers, making them flow like honey. Picture the spandex fibers in athletic wear or the tough plastic films in phone screens—DMF helped them take shape. Some of the strongest industrial adhesives owe their stickiness to DMF, allowing things to hold together under stress or pressure. If you’ve ever wrapped food with cling film, the flexibility and clarity probably exist thanks to this chemical.

Risks Worth Weighing: Worker Health and Environment

DMF isn’t just useful—it’s also risky. I remember safety meetings where DMF always landed on the agenda. Extended exposure can affect liver function and may even increase cancer risks, according to findings from the International Agency for Research on Cancer. Out in the environment, it doesn’t stick around for long, but spills can still harm aquatic life or contaminate groundwater. Responsible companies treat DMF waste in controlled setups, scrubbing vapors or trapping residues before anything hits the open air or sewer. Real improvements happened once regulations tightened and companies took worker health more seriously. Respirators, gloves, and closed-system reactors became the norm, at least in well-run plants.

Finding Safer Paths Without Slowing Progress

Regulators keep a watchful eye on how DMF gets used. Some sectors started switching to safer or less volatile solvents, where possible, and ramped up recycling systems to recover DMF after use. At the same time, green chemistry keeps pushing out new alternatives, making it possible for businesses to cut down on risks for workers and the planet. In my own experience, trials with new solvent blends showed early promise, but sometimes costs or lack of performance sent teams back to DMF. Progress takes honest commitment and a willingness to experiment. If real money and effort keep flowing toward safer substitutes and strict controls, tomorrow’s industries might be able to keep the best of DMF’s results without sharing its baggage.

Looking DMF in the Eye

Anyone who’s ever spent any time in a lab probably knows the sharp, fishy smell that drifts from a bottle of N,N-Dimethylformamide—often just called DMF. A lot of us work with it for making pharmaceuticals, plastics, or just running a stubborn HPLC sample. DMF’s polar nature makes it a go-to solvent for chemists, but it comes with risks. Ignoring the hazards because “everyone does it” doesn’t cut it, especially when research shows DMF gets into the bloodstream through skin contact and inhalation.

Why It’s Worth Respecting the Label

The label tells you a lot. DMF doesn’t just cause headaches or leave your hands feeling dried out. The facts are clear from studies: exposure can strike your liver, cause skin irritation, and even affect unborn children. Years ago, I watched a colleague develop a nasty rash after one quick splash. The reality hit home after reviewing a few MSDS sheets and realizing even short-term exposures add up. There’s no way to “power through” DMF’s risk with bravado or by opening a lab window.

Practical Steps Everyone Should Take

Let’s get real: gloves aren’t optional. Not all gloves create equal protection—latex lets DMF through fast. Nitrile brings better results, though butyl rubber stands as a clear winner. I always keep a box of butyl gloves handy and toss them when in doubt. If you notice a split or softness, swap to a fresh pair. Doubling up doesn’t hurt, especially if handling higher volumes.

Ventilation becomes as important as gloves. From what I’ve seen, too many try shortcuts, working open beakers on the bench. DMF vapor doesn’t stay put; you breathe it in before you realize. A good fume hood, sash pulled low, pulls vapors away. Never store DMF near heat sources. The vapors aren’t just unpleasant—they creep into your lungs, and chronic exposure stacks up.

Splash goggles feel clunky, but regular safety glasses don’t do enough. One drop can splash off the bench and find your eye. I keep goggles sitting next to the DMF—visible reminders help everyone remember. Aprons or coats, preferably chemical-resistant and laundered often, block splashes to clothes and skin.

Storage and Spills: Don’t Wing It

DMF belongs in tightly closed containers, far from acids and oxidizers. Flammable cabinets lined with spill trays make sure that even careless bottle placement won’t cause disaster. For transfer work, pump or pour inside a fume hood, and wipe down drips immediately with proper cleaning materials. Never use paper towels alone; DMF can soak through and linger.

Spills happen. Every lab I’ve worked in keeps spill kits with neutralizers and absorbents close. Everyone knows where to find them. If you get DMF on your skin, don’t just rinse “quickly”—strip gloves and rinse under running water for a full fifteen minutes, then talk to your safety officer. The same goes if someone starts feeling sick or dizzy: fresh air and medical attention, right away.

Building Habits That Stick

No shortcut beats real caution. Refresher trainings—yes, even the awkward ones—keep everyone sharp. Posting procedures for handling DMF at the entry of every lab where it’s used makes sure no one “forgets” what’s at stake. Encourage everyone to speak up when they spot unsafe practices; accountability saves more than embarrassment. If you buy, store, or handle DMF, keep yourself and your team actively engaged, every single time. The risk isn’t hypothetical. It’s real, and treating it that way keeps everyone safer.

The Basics: Remembering the Formula

N,N-Dimethylformamide carries the chemical formula C3H7NO. This formula means each molecule contains three carbon atoms, seven hydrogen atoms, one nitrogen, and one oxygen atom. Walk into any research lab or industrial chemical plant, and you’ll likely find someone using or at least talking about this compound. It’s one of those workhorse solvents that pops up for everything from making medicines to cleaning electronics.

Why Chemical Formulas Matter in Daily Research

Grabbing a bottle labeled N,N-Dimethylformamide isn’t enough. Chemists, engineers, and safety teams want clear identities — knowing the formula keeps people safe and precise. A lab mistake with misidentified formulas can end up ruining months of work or, worse, threaten someone’s health. The C3H7NO formula tells everyone exactly what they’re dealing with down to the atom, which helps avoid confusion, dangerous reactions, and wasted resources.

A Versatile Helper in Industry and Science

C3H7NO doesn’t just sit on a shelf. In the world of organic chemistry, it acts as a reliable polar solvent. Ask someone who makes pharmaceutical ingredients or polymers, and you’ll hear their relief at having a solvent that handles a wide range of compounds. Unlike many choices in the lab, N,N-Dimethylformamide stands out for dissolving both polar and nonpolar substances. You get flexibility that saves time and cuts costs, whether you’re scaling up production or tinkering with a new reaction scheme.

Concerns About Safety and Environmental Impact

Safety and stewardship guide every chemical’s use. N,N-Dimethylformamide comes with risks like skin absorption and toxicity. Prolonged exposure can trigger effects on the liver, so personal protective equipment and good ventilation are standard in labs and factories. Stories from workers who’ve handled DMF without gear tell a cautionary tale; some learned the hard way about headaches or nausea from poor ventilation. Mistakes raise real health flags, so companies have adopted strong protocols: gloves, goggles, and air handling systems get used every day around this solvent.

The environmental impact sparks its own debates. Factory managers working near rivers face local rules about controlling DMF waste. The formula might seem simple, but improper disposal unbalances ecosystems. DMF can break down in water or soil, but not fast enough for comfort. Adopting closed systems and advanced treatment technology protects both workers and neighbors — moving beyond bare compliance toward genuine responsibility.

Innovation and Practical Solutions

My time working around analytical labs taught me the value of ongoing training and updated processes. Regular hazard audits help keep up with new findings about DMF’s toxicity. Some labs have started switching to alternative solvents in less demanding applications, reducing dependency where possible without sacrificing performance. These changes grow from team feedback and scientific evidence, not just regulations. Collaboration between safety officers, chemists, and process engineers creates solutions that blend innovation with sensible caution. Communication and open data also keep safety records up and knowledge accessible in an industry frequently judged by its transparency.

Wrapping Up the Value of Knowing N,N-Dimethylformamide

For anyone in chemistry, C3H7NO represents more than a formula — it anchors decisions about efficiency, safety, and stewardship. Hands-on experience blending technical knowledge with common sense leads to better outcomes, both in daily work and for larger community health. Keeping an eye on the facts behind the formula makes a difference that lasts.

Why This Chemical Deserves Respect

N,N-Dimethylformamide, often shortened to DMF, gets used every day in laboratories, factories, and research centers. It's a key part of textile manufacturing, electronics, and plenty of pharmaceutical work. Most folks who handle it know it’s got power—they know about its unmistakable smell, its boiling point up around 153°C, and its knack for dissolving all sorts of stuff many other solvents can’t touch. What a lot of people forget, though, is that DMF isn’t just another bottle on the shelf. This liquid can make people sick, damage the liver, and pollute an indoor workspace in a hurry if stored wrong.

Temperature and Ventilation

In real terms, storing DMF comes down to two big rules: keep it cool, keep it aired out. The label might say “store in a cool, dry place,” and that’s not just window dressing. DMF evaporates easy. I’ve seen old, forgotten bottles lose a chunk of their contents in just a few weeks if left near a heat source. Leaving it under direct sunlight or near radiators speeds up this loss and turns the storeroom into a problem no one wants.

A dedicated flame-proof cabinet works best—especially one away from strong acids or bases. Too often, storerooms turn into crowded closets where incompatible chemicals stand shoulder-to-shoulder. DMF, with its flash point of 58°C (136°F), doesn’t like being surrounded by oxidizers or strong acids. I’ve learned the hard way that mixing up storage means extra risks nobody needs.

Containers Matter More Than You Think

The bottle itself makes a difference. Never use plain old metal cans. DMF attacks plain steel and many alloys over time, eating through lids and threads. Glass bottles with proper Teflon-lined caps make a solid choice; high-grade, sealed plastic containers (HDPE) handle it too. If the seal breaks or the cap cracks, DMF vapor drifts out. It doesn’t take much of that odor to warn—your nose knows, and indoor air quality drops fast.

Avoiding Spills and Keeping Track

A surprising number of labs run into DMF problems not because of leaks but from poor labeling and over-full bottles. Splashing pour lines, missing hazard labels, or a forgotten open cap—those tiny mistakes can add up. Real accountability means logging each use and double-checking lids before leaving at the end of the shift. Good training saves a lot of trouble here.

Health and Safety: The Personal Side

Nobody wants a splashed hand or a whiff of DMF on Monday morning. Many still walk into chemical stores without gloves, and that’s asking for trouble. Nitrile gloves and eye protection belong near any DMF bottle. Installing an eyewash station and keeping spill kits nearby isn’t overkill—it’s just looking out for yourself and your coworkers. I’ve seen how a small spill, wiped with a bare hand, can turn into a full day of headaches and worse.

Simple Steps, Safer Spaces

Keeping the cap tight, storing DMF away from heat, using the right bottle, double-checking labels, and wearing gloves—these daily habits do more than obey the rulebook. They lower risk and make for a workplace that’s just plain healthier. Regular stock checks catch old bottles before they become leakers. Local exhaust vents or fume hoods add another layer of protection, pulling vapors out so no one breathes in what they shouldn’t.

It doesn’t take fancy technology to store DMF safely, but it takes real attention and respect. Years working around chemicals teach you that a little care at the start saves endless headaches later on.

What Is N,N-Dimethylformamide?

N,N-Dimethylformamide, often called DMF, shows up regularly in chemical plants, labs, and certain manufacturing operations. Folks who work in places making plastics, synthetic leather, fibers, and pesticides cross paths with this solvent more than once during their careers. Its role in dissolving other chemicals makes it a convenient tool, but that ease comes with a plume of risk.

Risks to Our Bodies

Handling DMF means dealing with a substance that slides easily through skin and hangs around in the air as vapor. The first thing workers notice is the odd smell — some liken it to fish, others say it reminds them of ammonia. That whiff is a signal. Once the stuff reaches you, problems start. A little contact with DMF can trigger skin irritation, making hands itch or peel. Touch it every day without proper safety gear and the skin may start to break down, setting the stage for deeper health trouble.

The liver takes most of the beating. Health organizations such as the World Health Organization and the U.S. National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health identify DMF as a hepatotoxin. Even low levels, over time, can lead to elevated liver enzymes. Some workers in the chemical industry have developed hepatitis-like symptoms, such as yellowing skin and enlarged liver, after prolonged DMF contact.

Breathing in DMF vapor feels harsh. It can cause throat and lung irritation, headaches, dizziness, and sometimes nausea. Long-term inhalation runs the risk of damaging the liver and impairing lung function. Reports exist of workers developing chronic bronchitis after months of unprotected exposure. Away from the shop floor, few talk about how these symptoms chip away at someone’s day-to-day comfort and ability to work safely.

Concerns that Reach Beyond Plants

Several studies have asked what DMF does to the reproductive system. Research points toward fertility issues in both men and women, and there’s evidence that pregnant women exposed to this solvent risk miscarriages and birth defects. The European Chemicals Agency flags DMF as toxic for reproduction, urging strong controls in job sites using it.

Though the chemical doesn’t build up in the environment like some persistent pollutants, it moves easily through air and water. Accidental spills or poor ventilation in a community could reach beyond workers and affect families, especially in areas without strict safety rules or regular environmental monitoring.

Better Safety, Stronger Health

I’ve seen the difference safety practices make in factories. Respirators, proper gloves, eye shields, and regular breaks in clean air matter. Companies that monitor DMF vapor levels and rotate workers out of high exposure spots see fewer health claims and reduced sick days. It helps when workers stay trained to spot signs of poisoning early. No one should brush off symptoms or skip routine blood tests for liver health.

People shouldn’t face health risks alone. Union stewards can press for stronger air filtration. Management should make sure every worker gets tested for exposure yearly. Outside the plant, stricter limits set by agencies like OSHA keep companies honest and workers safer. Safer chemicals deserve a spot on the research agenda so that DMF eventually becomes a story of the past, not a daily worry in factories worldwide.