Chloroform: A Comprehensive Commentary

Historical Development

Chloroform’s story stretches back to the early 19th century, woven tightly into the beginnings of modern chemistry and medicine. In 1831, Samuel Guthrie, a physician in upstate New York, independently created chloroform while seeking better substances for anesthesia, soon followed by Justus von Liebig and Eugène Soubeiran in Europe. The substance entered the medical scene slowly, partly due to concerns about safety and the novelty of using chemical compounds for pain relief. James Young Simpson’s experiments in 1847 caught public attention, as he—and his friends—famously inhaled chloroform in a parlor, paving the way for its use during childbirth and surgery. For decades, chloroform shared the surgical stage with ether, but soon enough, the drawbacks mounted. Stories of fatal overdoses started trickling in, especially after high-profile deaths like that of Hannah Greener in 1848. Medicine gradually turned away from chloroform, searching for safer options, but its impact on chemical history remains undeniable.

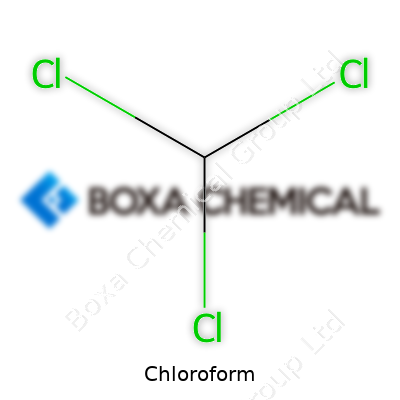

Product Overview

Chloroform rolls off the tongue as a common solvent and reagent, used everywhere from laboratories to industry. It looks and smells like something out of an old apothecary: a heavy, clear liquid with a sweet, lingering scent. In the world of chemicals, chloroform doubles as trichloromethane, a simple molecule—one carbon, one hydrogen, and three chlorines—yet powerful enough to reshape medical practice. Companies often list it with names like Methane, trichloro-; Methyl trichloride; or even R-20. For over a century, bottles marked “chloroform” seemed to show up anywhere someone needed to dissolve organic compounds, extract flavors, or work with synthetic rubbers and pharmaceuticals.

Physical & Chemical Properties

Chloroform’s nature stands out because of both its density and volatility. At room temperature, this clear, colorless liquid carries a density around 1.49 grams per milliliter—making it much heavier than water. It boils just shy of 62°C, making evaporation quick when air or heat gets involved. Its vapor, sweet and a bit sickly, tells a chemist’s nose it’s in the room long before it’s visible. It doesn’t mix with water, so it floats under most aqueous mixtures in the lab. From a chemical perspective, the molecule holds together firmly except under strong heat or in the presence of alkaline agents. Sunlight or oxygen brings out one of its darker features: slow decomposition into phosgene, a much more toxic cousin. The reactivity shows up in everyday tasks, too, as chloroform needs cold, shaded storage and regular checks for breakdown products.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Regulation keeps tight control over chloroform’s packaging and transportation. In many places, bottles feature hazard diamonds for acute toxicity and environmental danger, reflecting real and immediate risks. Common specifications require chloroform over 99% purity for lab applications, mainly to avoid stabilizer byproducts or trace acids from hydrolysis. Safety standards outline tight caps and brown glass containers to block light, along with clear batch numbers and expiration dates. Both lab and commercial buyers rely on correct labeling, as confusion with other clear liquids can spell disaster. Tracking documentation trails accompany each shipment, from customs declarations down to the end-user chemical inventory, to reduce unintentional release or misuse.

Preparation Method

Manufacturers usually produce chloroform by the halogenation of methane or chlorination of methyl chloride. In industry, the choice comes down to what base materials get handled most efficiently. A common method runs chlorine gas through boiling methane or methyl chloride, catalyzed by heat or ultraviolet light. The process demands strong controls to capture the evolving gases—mainly hydrochloric acid—generated alongside chloroform. Frequent monitoring guards against the halfway compounds, such as dichloromethane or carbon tetrachloride, sneaking into the product stream. In my experience, any slip in temperature or gas rate shifts product ratios quickly, so skilled operators make all the difference. Many smaller labs shift toward prepackaged chloroform rather than production, since handling chlorine gas introduces its own hazards.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

Chloroform doesn’t just dissolve other molecules; it steps into a host of organic reactions as both a reagent and a stepping stone. Chief among these: the Reimer-Tiemann reaction, where chloroform reacts with phenol and alkali to produce salicylaldehydes, critical in pharmaceutical synthesis. Reacting chloroform with strong bases spawns dichlorocarbene—a reactive intermediate that chemists wrangle for inserting carbon atoms into other molecules. Its breakdown, especially when sunlight touches even traces of air inside a bottle, results in a slow build-up of phosgene and hydrochloric acid, which underscores the need for careful disposal and stable storage. Anyone with hands-on chloroform work develops a healthy respect for these transformation pathways.

Synonyms & Product Names

In chemical catalogs, chloroform shows up under aliases: Trichloromethane, Formyl trichloride, Methenyl trichloride, or R-20. Some older or specialized lists label it as “Anaestheticum Chloroformium,” especially in historical medical texts. Across various languages, slight spelling shifts appear, but chemical identifiers stay steady. Researchers often sort chloroform by reagent grade, analytical standard, or solvent grade, each with purity tied to specific industry or academic thresholds.

Safety & Operational Standards

Handling chloroform asks for respect and vigilance. The inhalation risk dominates—symptoms range from dizziness and nausea to loss of consciousness or worse in case of high exposure. Its ability to depress the central nervous system made it both famous and infamous in surgical theaters. Today, labs outfit themselves with fume hoods, proper ventilation, and clear storage rules. Protective gear—gloves resistant to permeation, safety goggles, lab coats—ranks as non-negotiable shop-floor gear. Any accidental spill meets immediate containment, using absorbent materials and ventilated removal to keep vapors away from skin and lungs. Labor regulations roll out exposure limits: organizations like OSHA capping workplace air levels and mandating reporting for significant releases. Regular audits, inventory checks, and rigorous entry logs cut out casual or unsupervised access. Emergency instructions lean toward evacuation, ventilation, and rapid medical response.

Application Area

Chloroform carved out roles in several industries, medicine once leading the way. Its historical use stretches from anesthesia for surgery and dentistry to a solvent for extracting alkaloids in pharmaceuticals. Modern restrictions pulled back on direct human applications, but the chemical stuck around in manufacturing and research. Laboratories reach for chloroform to dissolve fats, alkaloids, and synthetic materials, or in DNA extraction protocols where phase separation counts. It helps in developing flavors, fragrances, and pesticides, or even in producing refrigerants and propellants—though many of these applications face restrictions coming from health and environmental reviews. Food and perfume industries moved away from chloroform in direct processes, yet its chemical fingerprints still turn up as intermediates. Water treatment plants sometimes check for chloroform as a byproduct of chlorination, emphasizing its continued presence in daily life.

Research & Development

Past decades brought new eyes to chloroform’s role, especially as research pivots toward less hazardous substitutes. Areas focused on green chemistry explore how to reshape solvent use, working on protocols that sidestep chloroform entirely. DNA researchers, for instance, now rely more on phenol-free extraction methods, or look to alternative organic solvents with lower toxicity. Industrial chemists also experiment with catalytic pathways that avoid chlorinated intermediates. Some technologists revisit older reactions, aiming to reduce phosgene risk with stabilizers or improved packaging. Chloroform’s analytical power still draws attention: in NMR (Nuclear Magnetic Resonance) spectroscopy, deuterated chloroform remains a standard solvent, balancing cost and spectral clarity. Teams across academia and industry monitor emerging evidence on trace exposures or environmental fate, feeding into regulatory updates and risk assessments.

Toxicity Research

Toxicologists spent years peeling back the dangers of chloroform. The compound’s old role in anesthesia masks a rabbit hole of adverse effects—acute or chronic. Inhaled in significant concentrations, chloroform can induce cardiac arrhythmia, liver or kidney damage, and, in extreme cases, sudden death. Long-term animal studies hinted at carcinogenic risks, pushing agencies like the IARC and EPA to designate chloroform a probable human carcinogen. Water supplies come under scrutiny, especially when chlorinated organics drift into municipal pipes. Health and environmental agencies now monitor chloroform levels closely, particularly near industrial discharges or improperly managed landfills. Worker protection advances directly from this research: stricter airborne standards, routine blood or urine monitoring, and lockstep with safety data. Any accidental exposure demands prompt treatment, best managed by teams familiar with both chemical antidotes and supportive care.

Future Prospects

Chemical practice circles around risk reduction, and chloroform’s future lies in a mix of redirection and replacement. Regulatory bodies keep trimming legal exposure limits, even as research flags up emerging threats from trace residues. Solvent innovation holds hope: greener mixes or solvent-free protocols lighten the load. Strict tracking from production to disposal helps cut down on illegal dumping or accidental environmental leaks. Emerging applications in niche chemistry—like advanced NMR studies—may preserve a tightly controlled window for chloroform use, surrounded by higher safety standards. For everyone else, training, transparency, and rapid adoption of safer substitutes remain the clearest path forward.

A Chemical with a Complicated Past

Chloroform hit the spotlight over a hundred years ago as a medical wonder. Anyone who has read a Victorian-era novel or paid attention in history class might recall it as the knockout liquid doctors gave during surgery. In that period, painkillers were limited, and anesthesia brought a sense of hope and relief. Chloroform entered operating rooms and even childbirth wards, offering what felt like a miracle—brief escape from pain and consciousness. Queen Victoria herself used it during childbirth, which fueled public trust.

Even though it worked fast, chloroform caused its share of tragedies. Doctors often had to guess doses. Some patients never woke up. Studies from those years linked it to heart problems and liver damage. By the mid-1900s, safer anesthesia drugs pushed chloroform out of hospitals. These days, doctors rarely, if ever, turn to it. Modern medicine keeps it for specific research and chemical processes.

Industry Holds Onto Chloroform

Factories and research labs still see chloroform as valuable. Its biggest role today comes from its power as a solvent. This means it dissolves other substances—oils, fats, waxes, alkaloids. Chemists extract penicillin and caffeine using chloroform, separating the desired product out of a tangle of natural chemicals. In my own college lab work, we used it for this type of extraction and separation. It worked fast and didn’t damage most of our samples, which helped us avoid wasting time.

Pharmaceutical companies also reach for chloroform in the background. Before medicines ever reach a pharmacy shelf, chloroform sometimes steps in during development. It has the right chemical properties for breaking down plant material and helping isolate molecules scientists want to study. Even with the risks, research protocols set strict handling rules—no one wants accidental poisoning or environmental contamination. University labs run elaborate ventilation and use sealed glassware for this reason.

Cleaning Up and Keeping Safety in Mind

The cleaning industry sometimes uses chloroform for tough stains or laboratory glassware, but never without oversight. The problem lies in its toxic fumes and potential to harm the liver and central nervous system. Inhaling chloroform, even by accident, damages human health. I remember a strict warning system in my lab—a whiff of “sweet-smelling” chloroform meant evacuation and an incident report. Facility managers keep it locked up, logged, and far from public reach.

Anyone using chloroform, even with gloves and goggles, needs to respect its danger. The Environmental Protection Agency tracks its release. Laws block careless disposal in drains or open air. Companies install chemical scrubbers in their exhaust lines, catching vapor before it escapes outdoors. Research facilities choose less hazardous solvents when possible. Training and regular audits keep everyone alert.

Is There a Better Way Forward?

Modern science always looks for safer paths. Green chemistry trends steer companies toward alternative solvents. Plant-based, biodegradable chemicals replace chloroform in some extractions and cleaning jobs. Regulators encourage this shift with tighter restrictions and incentives for safer methods. On the few fronts where chloroform can’t be replaced, industries invest in better storage, monitoring, and emergency response plans.

In the end, chloroform’s important uses rest on careful controls. History shows what can happen when convenience beats caution. Today’s experts hold education and strict protocols as their best safeguards, not just for those who work with chloroform but for everyone’s health and the environment.

The Reality of Chloroform in Everyday Use

Most people recognize the name “chloroform” from old detective novels or TV shows. The idea of someone waving a soaked rag and knocking a person out seems almost comical now, but the real substance is far less mysterious. Chloroform is a powerful solvent once used in medicine, and it still crops up in some industrial labs and research settings. Its track record, though, offers serious reasons to be cautious.

Why Chloroform Causes Concern

Short-term exposure to chloroform, even from evaporated liquid, produces numbness or dizziness. Sometimes it causes headaches or nausea. Longer skin contact means blistering and burns. Breathe enough of it, and the heart, liver, and kidneys start to struggle. I remember visiting a university chemistry lab in my student days—no one was casual with chloroform. Lab coats, thick gloves, and those hissing fume hoods were not just for show. Every one of us heard the same rule: respect the risk.

The U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) sets exposure limits at just 2 parts per million. That’s because chloroform can mess with how the body works after just a few big breaths. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) also tags it as a probable human carcinogen. Lab animal studies exposed to high doses developed tumors or suffered liver and kidney damage. None of this inspires confidence for casual use.

Common Uses and the Shift Away

Older doctors once used chloroform as an anesthetic, but that time passed for good reason. The death of patients in Victorian-era surgery rooms led medical boards to pull it from shelves. Today, chloroform appears in specialized jobs: lab researchers use it to extract DNA or purify samples, some industrial processes tap into its solvent power, and a few niche product manufacturers depend on its properties. No one trusts this chemical in wide circulation—chemists use it under tight controls.

What Safer Handling Looks Like

Safe handling asks for more than throwing on a pair of gloves. Anyone working with chloroform wears splash goggles and chemical-resistant aprons. Work stays under a fume hood so vapors drift outside instead of into lungs. Every open bottle creates a risk, so storage happens in sealed, labeled containers—away from heat and the reach of amateurs. Once used, waste must follow strict disposal rules. All of these precautions create layers of safety for people and the environment.

One of my colleagues once shared a story about inadequate storage leading to a spill. It took a solid afternoon, professional cleaners, and clear evacuation routes to manage the crisis. Protocols exist for a reason. Rushed or careless use almost always creates trouble.

What Could Improve Safety?

Better education reaches well beyond chemistry majors. Stories of near-misses should find their way into lab training for undergraduates, not just graduate-level workers. Access to alternatives should become easier. Many labs switched to less toxic solvents in routine work. More investment in those options and widespread sharing of best practices can make future work safer for everyone.

Personal vigilance, common sense, and sound regulations form the backbone of safety with chloroform and similar chemicals. There’s no shortcut. Small lapses often turn into emergencies. Most importantly, broad understanding—not secretive knowledge—may save lives and health in the long run.

Understanding the Threat

Chloroform may sound like a relic from a crime novel, but contact with this chemical still shows up in modern life. Most people run into chloroform through air or water, not during some dramatic event. It’s found near factories, in certain cleaning products, and even as a byproduct of chlorinated drinking water. I grew up near a plant that used industrial solvents, and stories about “mystery illnesses” on our street circled long before people realized environmental toxins can turn a neighborhood risky. Concerns about exposure are real, not some distant worry for factory workers alone.

What Can Go Wrong in the Body

Breathing air or coming into contact with water tainted by chloroform isn’t just unpleasant—it spells trouble for organs that nobody can ignore. Short-term exposure make people feel dizzy, tired, nauseous, and sometimes even lightheaded enough to pass out. But it’s the deeper effects that worry most toxicologists. Inhaling high doses or repeated exposure over time wages war on the liver and kidneys. That’s not something scientists discovered in distant animal studies; health records show people with higher chloroform levels in their drinking water tend to have higher rates of liver and kidney problems.

Chloroform turns into phosgene in the body, a toxic chemical that does slow damage. Both organs play cleanup crew for whatever enters your bloodstream, so damage shows up quicker than many realize. Some communities with older water pipes and heavy reliance on chlorine face higher exposure risks. I remember reading local reports about water testing in my old town, and neighbors started asking hard questions once cancer rates appeared above state averages.

Long-Term Exposure Isn't Just Scare Tactics

Chloroform stands on the list of possible human carcinogens, according to the International Agency for Research on Cancer and the EPA. Cancer isn't a rare scare: long-term studies across towns with higher chlorinated byproducts consistently find greater risks of certain cancers, especially bladder and colorectal. Researchers have pointed to byproducts like chloroform as one factor behind those numbers.

The brain isn’t safe either—a heavy dose knocks out the central nervous system, which is one reason chloroform was once pressed into service as an anesthetic. That history did not last long, once doctors linked exposure to heart problems and sudden death. It rattled more than a few medical pioneers.

Taking Action—Personal and Local Steps Matter

Avoiding unnecessary risk means small changes in habits and bigger changes in public policy. At home, a solid carbon block water filter knocks chlorine byproducts like chloroform way down. Making noise at city council delivers even more: regular water testing, replacing old pipes, and low-chlorine water treatment methods. People living near industrial sites might benefit from pushing for soil and air quality checks. Policy steps cost money, and sometimes progress crawls. But the fight for clean water and air usually starts with neighbors sharing their experiences, not just waiting for a corporation or government fix.

Everyone deserves to know what enters their home or workplace. Chloroform exposure didn’t get headlines for years. Lately, with more research and stronger public health standards, everyday people are picking up the slack to close that gap.

Why Chloroform Deserves Careful Attention

Chloroform sits on my shelf in the back of the lab—a sealed amber bottle, not much bigger than my hand. Every time I grab it, I remember how unforgiving this solvent can be. Some chemicals you learn once and move on. Chloroform sticks in your mind, because of its low boiling point, tendency to degrade in sunlight, and links to liver damage and cancer risk. These are not just details out of a textbook. Mishandling leads to exposure risks no one wants. You turn a cap a little too loose or forget its reaction with air, and you get phosgene, a chemical weapon from history.

Straightforward Storage, No Shortcuts

I’ve watched more than one student reach for chloroform like it’s just another jar of acetone. Every time I see that, it puts a knot in my stomach. Safety overrides convenience here. Chloroform belongs in a cool, dry place, far from light—even the stray beam that filters through blinds. Amber glass takes care of most of the sunlight, but an extra layer of cover, like a closed chemical storage cabinet, adds peace of mind. Air exposure remains an issue. Chloroform breaks down quickly in air, especially if there’s a flicker of light around. I always check my cap for a tight seal and store it upright. Never store near strong acids, open flames, or oxidizing agents—textbook mandates that hold up in any real lab.

The bottle needs a stabilizer. Most commercial chloroform arrives with a pinch of ethanol inside. Ethanol slows down that toxic phosgene formation. I never shake the bottle after pouring—just a quick, careful tilt, then straight back on the shelf.

Disposal: Protecting People and the Environment

I see stories in the news every now and then about hazardous spills, and a fair percentage could have been avoided by smarter disposal. You count every drop: Chloroform cannot pour down a drain or get tossed out with general trash, even if it’s just a splash at the bottom of a flask. One colleague once thought emptying the wash bottle in the sink seemed harmless—Cost a full afternoon to file the right papers and notify administration, plus the headache of wondering about contamination.

Disposing means labeling waste clearly. Don’t just write “solvents”—write “chlorinated organic waste” or just “chloroform waste.” Separate the waste jug with a screw cap, don’t take shortcuts with those “temporary” lids—I’ve seen them pop off after a day. Specialized waste pickups happen on a regular schedule. Universities and professional labs carry contracts for hazardous waste. That paperwork trail may feel like a hassle, but it beats an environmental report or a violation fine. Small businesses or home labs work with third-party hazardous waste handlers. You never save money by cutting corners here, since cleanup costs always run higher than disposal fees.

Safer Labs, Healthier Communities

Chloroform’s dangers are well understood, so there’s no excuse for guesswork. Proper PPE—gloves, goggles, and a fume hood—are non-negotiable. I’ve been asked if these rules feel tedious over the years, but the moment you slack off, a minor slip can turn into a health scare nobody wants. Labs block access to volunteers and students who haven’t completed training. I’ve seen that pay off more than once by stopping accidents before they start.

Science doesn’t always feel like a matter of public trust, but how communities handle toxins like chloroform matters for everyone’s health. Strong protocols mean fewer headaches in the long run—and everyone makes it home safe at the end of the day.

Chloroform and the Evolution of Anesthesia

People sometimes wonder if doctors pull out a bottle of chloroform before they put someone under for surgery. The truth is, chloroform belongs in the history books, not in modern hospitals. Back in the mid-1800s, doctors used it to help patients avoid pain. Stories from dusty medical texts fill in the details: Queen Victoria even used it during childbirth. That didn’t make it safe, though. Chloroform knocks people out, but it also brings a heavy toll. Liver damage, sudden heart problems, and unpredictable reactions haunted the people who used it and the doctors who gave it to them.

The Real Risks Behind Chloroform

Imagine lying in an operating room, breathing in a chemical that could just as easily stop your heart as numb your pain. That’s what happened to more than a few people in those days. During the 1800s and early 1900s, medical records documented how patients would slip into fatal arrhythmias—sudden, deadly changes in the heart’s rhythm—after inhaling chloroform. The risk of death wasn’t low, either. Published estimates from that period reached around 1 in 3,000 anesthetics. Those odds sound much too high by today’s standards, even by the standards of my own family’s tolerance for risks.

Anesthesia Today: Science and Safety

Modern medicine moved on for good reason. Anesthesiologists pick their tools based on rigorous evidence and safety data. Science opened doors to safer choices—agents like sevoflurane and propofol, which clear out of the body quickly and offer precise control. These drugs have given millions of people the chance to come out of surgery without lasting damage or fatal complications. Hospitals follow strict monitoring protocols, using heart rate monitors, oxygen sensors, and breathing machines to keep track of every change in a patient’s condition.

Why the Myths Stick Around

Mention chloroform and many people picture the dramatic handkerchief-over-the-face trick from old detective movies. That image lingers, even though hospitals wouldn’t dream of using chloroform in real life. I’ve spoken with older neighbors who remember tales from their grandparents, passing on stories where chloroform played a starring role. Medical classrooms don’t teach students to use it anymore; they focus on drugs that deliver stronger pain control and much better odds.

What Keeps Patients Safe?

Good anesthesia depends on teamwork, careful science, and strict oversight. Agencies like the U.S. Food and Drug Administration keep a close eye on what doctors use. Hospital pharmacists and anesthesia providers review every medication for possible risks. In my own brief hospital stays, I’ve felt more confident knowing there are protocols and professionals in place. For anyone who wants extra peace of mind, it’s always possible to ask anesthesia teams about the medicines they use and why. Transparency and patient safety matter more now than ever.

Looking Beyond Chloroform: Building Trust in Care

Older ideas and outdated drugs fade because they no longer match what patients deserve or expect. Chloroform tells a story about how far medicine has come. Life brings enough uncertainty without facing outdated risks on the operating table. The commitment to patient safety keeps doctors and researchers looking for better answers, not fixes from the past.