Caprolactam: The Journey, Character, and Impact

Historical Development

Caprolactam traces its story back to the early twentieth century, a period restless with industrial ambition. German chemist Hermann Staudinger, often regarded as the father of polymer chemistry, made crucial advances that set the stage for commercial synthesis. The push to discover alternatives to silk spun up the first large-scale production efforts. Post-war economies quickly recognized the appeal of a material that could feed the growing demand for synthetic fibers. Companies ramped up research budgets, plants sprouted across Europe and North America, and caprolactam became the backbone of nylon 6 production. Its importance grew every year as clothing, car parts, packaging films, and industrial yarns entered daily life. The chemistry benefitted from relentless work throughout the sixties and seventies, especially as environmental concerns grew louder. Researchers fine-tuned its preparation from cyclohexanone and other feedstocks, narrowing in on process efficiency and waste reduction. This blend of history and science laid the foundation for caprolactam’s current status as a cornerstone of modern manufacturing.

Product Overview

Caprolactam often lands on palettes as a white, crystalline solid or appears as a clear liquid above its melting point. Its main ticket to fame comes from its use as the sole precursor for nylon 6, a polymer that shaped entire industries. Beyond textiles and carpets, it shapes monofilaments, engineering plastics, and countless everyday items that people might never guess trace their origins to such an unassuming chemical. After nearly a century of refinement, production reliability and purity have reached heights that keep nylon-based materials sturdy, trusted, and competitive in everything from apparel to aerospace.

Physical & Chemical Properties

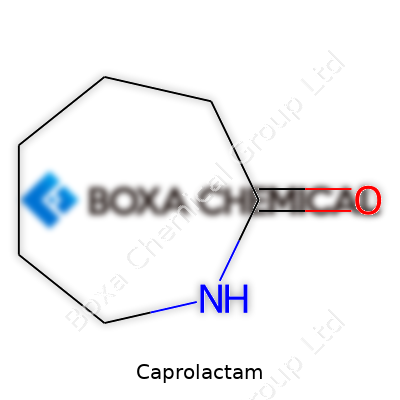

Caprolactam’s molecular formula, C6H11NO, gives it a straightforward ring structure, a seven-membered heterocycle. Its melting point hovers near 70°C, boiling just above 260°C with notable sublimation, which sometimes challenges storage protocols in hot climates. Slightly soluble in water and mixing well with most organic solvents, it offers notable versatility. Its moderate hygroscopic nature sometimes creates headaches for shipping, as it will absorb moisture given the chance. Because of this, quality checks for water content take priority for anyone using it in polymer production, since even minor contamination can ripple through subsequent processing steps. Its reactivity springs up when exposed to acids or bases, making equipment selection and handling practices important for safety.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Markets demand caprolactam at precise purities. Most buyers expect purity endorsements beyond 99.5%. Manufacturers rely on advanced analytical tools—gas chromatography, titration, spectroscopic methods—to guarantee batches stay within tight specification windows. Shipping containers carry labels that comply with international norms, usually referencing CAS number 105-60-2, hazard statements in line with GHS standards, and guidance on safe handling and storage. Documentation threads through every step, starting at plant dispatch and not leaving a product until it lands at the customer's facility. Strict expiration dates and storage temperature guidelines stamp every bag or drum, keeping both safety and performance in focus.

Preparation Methods

Caprolactam production starts with cyclohexanone, which undergoes an oximation reaction with hydroxylamine. This forms cyclohexanone oxime, which then navigates a Beckmann rearrangement, shuttling the molecule into caprolactam territory. Major plants favor continuous processing, coaxing higher yields and lower energy footprints. Different companies keep tweaking the recipe, swapping catalysts, improving energy recovery, and squeezing out by-products like ammonium sulfate—a key fertilizer ingredient. Every research paper that manages to cut greenhouse gas emissions or chop waste output finds a ready audience. Achieving competitive cost while juggling efficiency, safety, and environmental impact drives innovation across the industry. Engineers track every heat exchanger and reactor for performance, never losing sight of process safety and environmental compliance.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

Chemically, caprolactam demonstrates a knack for ring-opening polymerization. Heating sets off an opening of the lactam ring, and caprolactam molecules link up as polyamide chains, forming nylon 6. Chemists also find value in its intermediate role, modifying the molecule with functional groups to explore specialty resins and copolymers. Surface functionalization steps let nylon gain water repellency, flame resistance, or better binding with metal and glass fibers. This flexibility underpins the diversity of end uses: a single monomer points the way to everything from fishing line to precision automotive gears. Lab researchers keep hunting for new modifications to boost recycling, reduce environmental load, and match shifting regulation.

Synonyms & Product Names

Caprolactam goes by several aliases, showing up in documents as 1-azacycloheptan-2-one or 2-oxohexamethyleneimine. Some trade circles dub it aminocaproic lactam. Buyers and regulators know it by its CAS number, 105-60-2, to dodge confusion. Downstream, once polymerized into nylon 6, the legacy stretches out through trade names owned by sector titans—Nylon 6, Perlon, Capron—each offering their own blend of additives and properties. This web of product naming keeps supply chains flexible but sometimes sends new buyers hunting for clarity.

Safety & Operational Standards

Factories that handle caprolactam follow layers of safety regulations. Inhalation or skin contact irritates, so ventilation systems run strong and operators wear gloves, goggles, and respirators as a rule. Regulatory bodies such as OSHA and REACH set thresholds for airborne concentrations. Spill response steps are drilled into every crew. Material Safety Data Sheets back up every container, spelling out flammability risks and emergency first aid. OSHA designates caprolactam as hazardous, though it doesn’t pose major acute toxicity threats at standard exposure levels. Still, factory managers train their teams as if the stakes run high, knowing that a slip in handling protocols can trigger accidents or environmental violations, and quality and safety audits chase any sign of lapses. Years of industrial accident reports have sculpted the current best practices, and any major producer stays sharp on compliance to dodge fines and reputational hits.

Application Area

Nylon 6 stands as the main legacy of caprolactam, unraveling into fibers for carpets, sportswear, and tire cords. Car makers lean on nylon 6’s resistance to abrasion and chemicals, putting it to work in engine covers, timing belt fabrics, and air intake manifolds. Food packaging picks nylon 6 for barrier properties, keeping oxygen and odors at bay. Electrical goods rely on caprolactam-based engineering plastics to strengthen cable sheaths and home appliance components. Caprolactam even enables specialized adhesives, hot-melt glues, and medical devices, riding on its balance of mechanical strength and processability. Water purification, filtration, and construction see action from caprolactam derivatives. Every passing year, new uses crop up, nudged along by changes in consumer habits and advances in additive technologies.

Research & Development

Labs and industry teams pour resources into greener, cheaper, and cleaner methods for making caprolactam. Bio-based production has grabbed momentum, using engineered microbes to turn plant sugars into raw materials. Improvements in catalyst recycling and step integration help grind down energy costs and lower emissions. Researchers also study recycling of nylon products back into caprolactam, closing the materials loop and stretching the resource pool—an approach that fits right into modern circular economy models. Big players challenge their chemists to slash water consumption and develop purification processes with less chemical load. Modifications to the lactam structure create high-performance polymer grades or smart materials for medical and electronics fields. Every technical report and patent in this direction points to a future where caprolactam’s carbon footprint shrinks and its utility spreads even wider.

Toxicity Research

Caprolactam’s potential health impacts have not gone unstudied. Under standard handling, acute toxicity stays low, though the substance irritates skin and eyes, and substantial vapor exposure can trouble the respiratory tract. Early research mentioned concerns about carcinogenicity, yet repeated animal studies have not established a strong link under realistic exposure conditions. Environmental concerns focus more on the run-off from manufacturing plants, which can load nearby water with ammonium by-products or small traces of organics. Fish and aquatic invertebrates bear the brunt if chemical containment fails. This has led to tighter wastewater controls, constant monitoring, and a push for process innovations that cut effluents at the source. Ongoing studies track the effect of chronic low-level exposure on factory workers in regions with large-scale production, aiming to reassure regulators and communities.

Future Prospects

Every big materials shift of the past century rode on fine-tuned chemistry, and caprolactam finds itself at another turning point. Producers in China and India keep leapfrogging older plants, bringing high-efficiency units online with lower per-ton emissions than ever before. Renewable feedstocks and closed-loop recycling set the course for a more sustainable value chain. Consumer pressure for ecologically sound products pushes researchers into partnerships with universities, all hunting for drop-in bio-based versions that offer the same processing and performance perks. Governments fund pilot projects to turn landfill-bound nylon waste into fresh caprolactam. As new markets demand lighter, tougher, and greener materials, caprolactam chemistry stands ready—so long as industry keeps responding with invention and respect for ethical, safe, and responsible manufacturing practices.

A Fiber That Shapes Our Daily Life

Caprolactam might sound like just another tongue-twister from a chemistry class. For most people, this compound rarely crosses the mind, yet it connects tightly to what we put on and what surrounds us. Most of the world’s caprolactam goes straight into making nylon 6. That means if you have ever worn a nylon jacket, zipped up a tent on a rainy night, or watched your kids play with plastic toy cars, some version of this compound likely touches your life. Nylon 6 isn't a status symbol or something you’ll see in glossy ads. It shows up in sturdy, everyday goods—clothing, carpet, industrial cords, even the strings that hold up tennis rackets.

The Global Reach of a Simple Compound

Annual worldwide production of caprolactam sits in the millions of tons. Researchers at Grand View Research reported that nylon 6 demand keeps rising, with the fiber segment holding the largest share. Factories in China, Europe, and the US keep round-the-clock operations to supply hungry industries. That demand pulls in enormous amounts of raw materials such as cyclohexanone and ammonia, spurring supply chains that stretch from oil refineries to small textile workshops.

Environmental Cost That Demands Attention

I grew up in a town where the river sometimes ran with a strange, milky color. Many old factory workers blamed leaks from the local chemical plants. Caprolactam production doesn’t just stop at the finished product. Wastewater, air emissions, and solid waste from these plants raise real concerns. Reports from the European Chemicals Agency draw clear links between the production process and risks for aquatic life. Even though many facilities follow regulations, both accidents and poor oversight have resulted in stubborn pollution. The industry has been working on closed-loop systems and better recovery, but what goes down the drain still matters.

Health Risks Around the Edges

Caprolactam workers run into chemical dust and vapors every shift. The US National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health suggests protective work routines, but not all plants follow best practices. Short-term exposure can irritate eyes or throat, while long-term risks remain under review. Even for people outside these plants, the chemical can reach water and soil in small doses. More research ought to keep pace with expanding production, and health agencies need steady checks on safety limits.

Searching for Smarter Solutions

Synthetic fibers won’t disappear overnight, so it makes sense to focus on smarter practices. Cleaner technologies have arrived—modern plants recycle more water, scrub exhaust more thoroughly, and convert waste byproducts into useful chemicals. Brands like Adidas and Patagonia have started blending recycled nylon into their gear. Developing economies fund pilot projects for bio-based caprolactam, aiming to cut fossil-fuel dependence. These changes ripple through the industry, but real progress happens only when regulators, producers, and consumers all push for it.

What’s Next for Caprolactam

In the end, caprolactam stands as more than a building block for synthetic fibers. The way industries handle it says a lot about our willingness to rethink habits. If communities keep asking for transparency and safer products, the market will shift. Until then, most people will keep unzipping their jackets and stretching their yoga pants, paying little mind to the chemistry woven through daily routines.

Chemical Formula and Structure

Caprolactam carries the formula C6H11NO. It forms the backbone of nylon-6, a material woven into fabrics, carpets, and even car parts. With six carbons, eleven hydrogens, one nitrogen, and one oxygen atom, the structure seems simple, but the ripple it creates in daily life is anything but. Chemistry students might just memorize this formula for an exam, but those of us working around materials science have seen how deeply it connects to the stuff we touch every single day.

Everyday Use: From Factory to Fiber

Factories around the world depend on caprolactam. The global market chews through millions of tons every year. Workers turn it into nylon-6, not for novelty, but because this material handles stress, weather, and friction better than cotton or polyester. Walk down a grocery aisle—nylon-6 lines food packaging. In the kitchen, spatulas and utensils stay flexible and tough because caprolactam started the process. Plenty of industries—furniture, automotive, construction—lean on nylon-6 because of the way it resists wear and holds shape.

Environmental Concerns

The mass production of caprolactam leaves a footprint. Plants often release greenhouse gases and produce ammonium sulfate as a byproduct. That byproduct needs careful handling: runoff pollutes water sources, plant emissions drive air quality concerns, and waste ends up overwhelming local systems. It calls for real vigilance, not just from regulators but also from the people working the factory lines and the management overseeing these operations.

Health and Safety Risks

Caprolactam itself can be an irritant, especially in powder or vapor form. Short-term exposure might sting the eyes, tickle the throat, or cause headaches. Long-term risks mount for those without good protective gear or proper ventilation. In my work on the shop floor, respiratory masks and regular safety training help keep people safe. The chemical’s manufacturing process involves high temperatures, pressure, and sometimes hazardous reagents. Accidents can have harsh effects, both immediately and over time.

Solutions and Progress

Industries learned some lessons the hard way. Cleaner production technology—like advanced scrubbers, closed-loop reactors, and improved water treatment—reduces pollution. Pushes toward recycling nylon-6 come not just from environmental officers but also from big clothing brands. Repurposed ocean plastics feed back into the supply chain. Innovations using bio-based caprolactam, made from plant sugars rather than fossil fuels, show promise. Adoption remains slow, as costs remain high and yields lower compared to petrochemical routes. Still, investment signals a serious intent to do better.

Industry Responsibility and Our Choices

Manufacturers hold much of the power, but end users also shape demand. Fashion brands have begun to favor recyclability and transparency in sourcing. In my own life, choosing goods made from recycled fibers—or simply using less—makes a dent, however small. Public pressure and nonprofit groups keep these conversations alive in boardrooms and legislative halls.

The Bigger Picture

Caprolactam, with its formula C6H11NO, keeps global supply chains running, but it also puts serious questions on the table about balancing progress and sustainability. Scientists, workers, and everyday consumers share in the responsibility. Understanding the science behind our daily materials brings some humility and a deeper push to ask—not just what invisible chemicals do for us, but what they mean for our shared future.

The Reality Behind Handling Caprolactam

Caprolactam doesn’t stand out in everyday conversation, but it plays a massive role in the world of nylon. Most folks who spend time in an industrial setting have crossed paths with this chemical. It’s found in the production of nylon fibers used in everything from clothing to car parts. The real concern comes when you examine what it means to work around caprolactam day in, day out.

Health Concerns That Deserve Attention

Hands-on experience in factories that process caprolactam shows that this substance deserves respect. When heated or handled carelessly, it releases fumes that can irritate eyes, skin, and lungs. The strong, almost fishy smell gives fair warning, but not everyone catches on fast. According to data from the U.S. National Library of Medicine, people exposed at work have reported burning eyes, runny noses, and even headaches. Short-term effects usually disappear once you get fresh air. Prolonged or high exposure, though, can leave you with worse symptoms—skin rashes, chronic cough, and in some particularly unlucky cases, asthma.

I've listened to friends complain after working a full shift near caprolactam reactors—nothing too dramatic, but their stories always sound the same: red skin, scratchy throats, watery eyes. Wearing the wrong gloves or skipping protective gear only makes things worse. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) set clear limits on exposure: don't breathe in more than 1 mg per cubic meter over an 8-hour shift. That isn’t just bureaucracy talking; it’s based on piles of research.

Fire, Spills, and Environmental Worries

Caprolactam itself doesn’t burn easily under normal conditions, but the dust and fumes from manufacturing sites create fire risks. If spilled, it’s no simple cleanup. If the powder finds its way into waterways, aquatic life isn’t happy; fish and other fragile species can get hurt. I remember a local river near a plant once had a fish die-off after a minor spill. The strict waste management processes in most chemical plants show just how seriously companies take these risks.

How Teams Stay Safe

Protection has always felt best when teams treat safety as second nature. Most of my experience tells me that simple habits make the real difference: gloves, goggles, and good air flow. Washing thoroughly after shifts goes a long way. The companies that do best set up training, keep people alert about symptoms, and post real reminders—not just faded posters in the breakroom.

Across the chemical industry, leaders like BASF and Invista focus on prevention, not just response. Closed systems and careful containment reduce the need for workers to come face-to-face with fumes or dust. Regular checks for leaks, air monitors, and emergency plans have all become as routine as clocking in. These habits keep the problems small.

Better Solutions for the Future

What would change the game is better engineering controls and stronger accountability. More automation in manufacturing can keep workers further from the riskiest points of contact. Sharing exposure data across companies and countries tightens up best practices. Simple investments in better ventilation pay off; so do ongoing health checks for workers. Many small manufacturers could benefit from collective industry guidance since not every workplace has the budget or know-how of global leaders.

Caprolactam is useful, but careless handling isn't an option. Most issues come down to human experience—seeing the warning signs, knowing the right steps, and being part of a group that values safety above shortcuts. That’s the difference between a workplace that gets by and one where people trust the process.

Building Blocks for Everyday Products

Caprolactam keeps showing up in surprising places. At its core, it plays a lead part in the production of Nylon 6, a material that pretty much everyone has handled at some point. Just think of carpets, automotive parts, textiles, and even sportswear—most of these borrow their strength and flexibility from Nylon 6. This single-use case makes caprolactam an industry giant. Take the carpeting in homes or offices: Nylon 6 fibers help these floors handle daily wear, pet claws, spilled drinks, and heavy foot traffic. In the clothing world, lightweight but tough sports leggings and jackets become possible because of this compound.

Reliability on the Road

Automotive makers depend on polymers derived from caprolactam for both performance and safety. Car manufacturers want materials that can deal with heat, friction, and the occasional knock or bump. Engine covers, gears, radiator fans, and fluid reservoirs built with Nylon 6 benefit from caprolactam’s reputation for toughness and heat resistance. Instead of using metal, which can rust and add weight, car makers pick caprolactam-based plastics to cut down on costs, improve fuel economy, and make vehicles safer for everyone.

Saving Energy and Reducing Waste

Caprolactam isn’t just about convenience or design. With the world moving toward lower emissions and less waste, caprolactam-based materials have started showing up in food packaging. Films and containers produced from these plastics create barriers against oxygen and moisture. This matters in supermarkets, where keeping meat or cheese fresh reduces food waste and gives people more time to use what they buy. Since these materials can be recycled, industries find another way to leave a lighter mark on the environment while meeting customers’ basic needs.

Supporting Health and Safety

Healthcare workers use equipment made with caprolactam every day. Medical devices, syringes, surgical threads, and simple protective coverings all draw on its tough but flexible nature. Hospitals need gear they can trust—something that won’t fail at a critical moment. Caprolactam-based products offer a strong, sterilizable, and lightweight alternative to metal or glass. Since pathogens can’t survive on properly sterilized plastics, medical facilities cut down infection risks, keeping both staff and patients safer.

Seeking Solutions for the Future

Most applications depend on petroleum, and that puts caprolactam in the spotlight as industries push for greener solutions. From personal experience following the shift toward sustainability, I’ve seen chemical engineers and researchers focus on finding bio-based or recycled sources as an alternative starting point. Some companies invest in circular economies—recycling old Nylon 6 textiles into fresh supply chains—lowering carbon footprints while meeting global demand. With tighter regulations and consumers watching what goes into everyday goods, manufacturers face real pressure to improve processes and offer clearer information about chemical safety.

The Road Ahead

Caprolactam supports more than just fiber and plastics. It changes the strength, durability, and performance of ordinary products. Factories, designers, and consumers each have a role protecting workers and the environment as the material’s use keeps growing. Innovations in source materials and recycling could set new industry standards and protect health and safety for years to come.

Caprolactam’s Journey Starts in Oil Refineries

Caprolactam lives behind the scenes in everyday items—carpets, clothing, fishing nets. Most people who use nylon products never think about what kicks off their life: a chemical called caprolactam. Factories usually start with a raw material called cyclohexanone. Refineries make cyclohexanone from phenol, itself a result of crude oil’s long voyage from deep underground to plastic milk jugs and so much more.

Turning Cyclohexanone into Caprolactam

Chemists take cyclohexanone and react it with ammonia and oxygen. This isn’t simple. Industrial reactors keep conditions hot and pressured so that cyclohexanone and ammonia connect to make cyclohexanone oxime. This reaction produces byproducts like water and heat. Managing heat matters a lot—too much, and equipment gets damaged. Too little, and production drags to a halt. Factories rely on careful control, along with experienced chemical operators watching the numbers day and night.

Afterward, plants send the oxime into contact with sulfuric acid. This rearranges its atomic structure through the “Beckmann rearrangement.” The reaction flips atoms around and transforms the oxime into caprolactam. Scientists figured out this step over a century ago, but tweaking the right acid concentrations and temperatures for industrial efficiency took decades of real-life trial and error.

Cleaning Up and Moving Forward

Caprolactam isn’t immediately ready for the world. The acid mixture left after the reaction still holds a lot of impurities and leftover chemicals. At this point, operators rely heavily on washing, neutralizing, and purifying steps. Water, solvents, and specialized ion exchangers strip away unwanted leftovers. What comes out—finally—is a white, waxy solid. That’s the solid base for nylon 6, which factories melt and spin into wide-ranging products.

The industry faces strong pressure to reduce waste and pollution. Making caprolactam produces a fair amount of ammonium sulfate, a fertilizer that can pile up. Companies work hard to sell this byproduct or limit its creation by recycling ammonia within their systems. Wastewater treatment technology has improved since stricter rules appeared in the 1970s and 1980s. Reusing water, capturing heat, and cutting nitrogen emissions all help factories stay within environmental limits.

Safety and Transparency Matter

Working around hot acids, high-pressure systems, and volatile chemicals takes focus and training. Industry standards—a result of both accidents and honest reporting—mean frontline workers use personal protective gear, ventilation, and automatic monitors. Chemical manufacturers that share their safety records openly and admit their mistakes, rather than hiding them, end up more trusted both in their communities and across the market.

Better Caprolactam Means a Cleaner Tomorrow

Researchers and plant managers alike keep searching for cleaner ways to make caprolactam. Some chemical companies experiment with bio-based routes, trying to skip petroleum altogether by using plant feedstocks. These new methods still face scale challenges. But the push for greener chemistry comes from both public demand and realistic planning. Anyone who uses nylon, really, has a stake in how caprolactam gets made—and how our choices impact water, air, and the people living next door to every factory.